On July 4th, 2025, while millions of Americans were celebrating Independence Day, the Bitcoin network recorded one of the most striking moves in its history: 80,000 BTC — over $8.6 billion at today’s prices — were transferred almost simultaneously from eight addresses that had been dormant for more than 14 years. Each wallet held exactly 10,000 BTC, a perfectly round number typical of Bitcoin’s early years, when mining large amounts was far more accessible.

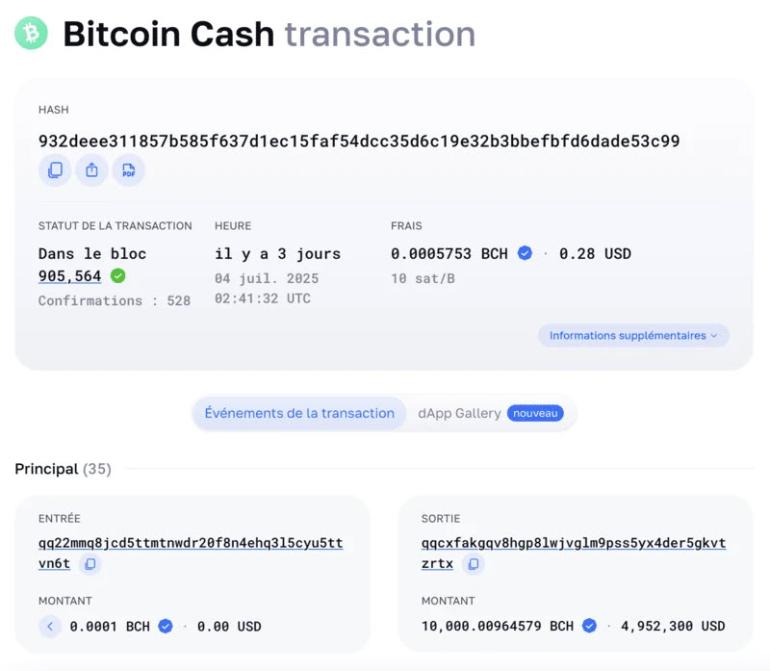

What makes this event so remarkable isn’t just the amount. It’s the fact that these addresses, created between 2010 and 2011, had never moved a single satoshi in over a decade. And the transfer wasn’t silent: before the main Bitcoin move, equivalent funds were moved in Bitcoin Cash (BCH), which would — at least on the surface — confirm that whoever did it holds the original private keys.

(For context: Bitcoin Cash (BCH) emerged in 2017 from the infamous blocksize wars, one of the fiercest debates in Bitcoin’s history. The community split between those who wanted to keep blocks small — favoring decentralization and ease of validation — and those who pushed for larger blocks to allow cheaper, faster transactions on the base layer. BCH was born from that split, and it shares the entire key history up to 2017. So moving funds first in BCH is like testing the key in a “divergent twin” of Bitcoin: it proves real control of the private key without touching the main BTC funds.)

In addition to this technical rehearsal, the orchestrators left a symbolic trail embedded on-chain. They did it using OP_RETURN, a special Bitcoin field that allows you to inscribe small pieces of text permanently. Since 2013, OP_RETURN has been used as a kind of “blockchain graffiti” — from simple contracts to memes or protest statements. This time, it carried legal notices, warnings about “abandoned” addresses, veiled threats of adverse possession, and even pop-culture nods to Lost. All wrapped in a carefully crafted narrative, including the creation of a legal front (Salomon Brothers) that invokes the idea of adverse possession for abandoned digital property.

To top it all off, they inscribed the famous sequence 4 8 15 16 23 42, known by millions of Lost fans. (In the series, these numbers repeat obsessively and must be entered every 108 minutes to prevent a supposed disaster that’s never fully explained. It’s a pop-culture wink, a reminder that secrets sometimes stay buried — and a cultural signature that makes the whole operation feel even more like performance art.)

Put simply: BTC that most people assumed lost forever moved again, and in a way that defies the usual logic of how early holders — Bitcoin’s OGs — typically behave. The immediate speculation was inevitable: are we witnessing the return of an early miner who never lost their keys? Or is this the first public demonstration that it’s possible to reconstruct private keys for very old addresses? Or, more cynically, is it just a carefully staged performance to legitimize an opportunistic appropriation without any real vulnerability?

There’s no definitive evidence for any of these explanations. The only undeniable fact is that the move happened, that it was technically valid, and that its coordination and symbolism suggest a plan far more elaborate than a simple recovery of old funds. From there, the question naturally follows: what would happen if the vulnerability theory proved partly true — even if only for a subset of keys generated with poor practices in Bitcoin’s earliest days?

The first point to grasp is the difference between a protocol failure and a weakness on the edges. Bitcoin’s network and consensus mechanism remain intact — the 21 million BTC limit is unchanged. No private key exploit could mint new coins or rewrite confirmed blocks. What could happen — in a scenario where lost or poorly generated keys are “recovered” — is that the liquid supply grows: funds that the market assumed permanently destroyed could return to circulation. This wouldn’t break programmed scarcity, but it would reshape perceptions of how many BTC are really spendable.

That nuance matters. For years, it’s been estimated that 10%–20% of all Bitcoin supply is lost forever — hard drives thrown away, printed keys never safeguarded, seeds never written down properly. This unintentional burn feeds the hyper-scarcity narrative: every lost bitcoin is, in practice, bitcoin no one else can ever spend. If fossil addresses can be reconstructed, some of that “dead” supply could come back to life. The result? More real liquidity — and more incentive to audit and move funds that sit inactive but technically exposed.

Another key angle is psychological. Bitcoin has always rested partly on the idea that “your key is your money.” That remains true — but events like this are a reminder that it’s not just about having a key: it’s about how that key was generated, and how resilient it is to attacks no one imagined a decade ago. Veteran users know that ECDSA, Bitcoin’s elliptic curve signature algorithm, hasn’t been broken. It’s one of the most audited cryptographic standards in use. The real risk lies in sloppy original generation: defective key generators, paper wallets with poor entropy, brain wallets with absurdly weak passphrases. (ECDSA itself is solid; it’s the human factor around key generation that cracks open vulnerabilities.) This is well documented — but seeing it happen on this scale puts it back on the table.

So, does this shatter trust in Bitcoin? Hardly. The most likely — and healthiest — reaction is for the community to double down on security: migrate old addresses to modern formats, use hardware wallets with properly safeguarded seeds, and remember that the real threat to custody isn’t cryptography — it’s human carelessness. Bitcoin’s network is built to withstand partial failures; the idea that some dormant BTC might return to circulation is real, but its structural impact is limited compared to a user base that now manages keys with standards that didn’t even exist 14 years ago.

Perhaps the most fascinating part is what this says about Bitcoin’s cultural evolution: a living network, one that doesn’t depend on every satoshi staying where it “should” — but on every satoshi that moves doing so according to consensus rules. There’s no undo button, no backdoor, no referee to “fix” uncomfortable history. If it’s ever shown that a group managed to crack fossil addresses, the debate wouldn’t be whether the protocol failed, but whether the community should react politically: forks, blacklists — or acceptance that reality on the blockchain is final. For many, the answer is clear: in Bitcoin, code and immutable history matter more than moral convenience.

In the end, the lesson that remains is bigger than speculation about exploits or cracked wallets. No BTC is truly yours unless you have real, present control of the key. And no key, however perfect it seems, might be invulnerable if its origin was weak. The question this story leaves open isn’t whether someone cracked 80,000 BTC — but how many other ancient addresses might lie within reach of those determined enough to reconstruct lost entropy. It’s a reminder to re-examine how, where, and to what standards you protect what, for many, is more than money: it’s living proof that true scarcity is defended not with dogma, but with technical responsibility.